The other side conceded this essential fact.

Friday, November 18, 2022

CHINA, INTERNATIONAL CHILD ABDUCTION, AND EXPERT TESTIMONY

Thursday, November 17, 2022

DOMINICAN REPUBLIC: EXITING WITH CHILDREN

Jeremy D. Morley

Children who are either citizens or legal residents of the Dominican Republic cannot be taken outside the Dominican Republic without full compliance with the Dominican Migration Department rules. This applies even for dual citizen children.

Those

requirements are as follows:

1. If

the child is traveling with both parents, they merely need to show their

passports.

2. If

the child is traveling with only one parent, the parent must have obtained

specific prior authorization from the Dominican Migration Office, which

requires the properly notarized consent of the non-traveling parent, obtained

from the Dominican Attorney General's office, if the party is in the country,

or the nearest Dominican Consulate if the party is outside the country. In the

latter case, the counselor authorization must be apostilled by the Dominican

Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Even if the traveling parent has sole custody of

the child, that parent must bring the travel authorization of the other parent,

unless the traveling parent has an express travel authorization issued by a

Dominican court.

3. If

only the child's mother has parental rights over the child, then it is sufficient

for her to produce the child's legalized birth certificate if she is

accompanying the child.

These rules apply even if

the child has dual nationality. They do not apply if the child has non-Dominican

citizenship only.

Wednesday, October 19, 2022

Japan’s acceptance of child abduction treaty leaves pre-Hague parents in limbo

By

MATTHEW M. BURKE AND KEISHI KOJA

STARS AND STRIPES • October 19, 2022

https://www.stripes.com/theaters/asia_pacific/2022-10-19/japan-parental-child-abduction-hague-7740130.html

In the 10 years since Donny Conway’s daughters Christina and Chihiro were taken by their Japanese mother to her home country without his consent, he has kept their bedroom in his California home filled with unopened Christmas presents, handwritten notes and reams of legal documents, he said.

The former Navy petty officer second

class is one of hundreds of American parents whose children were abducted by

another parent and taken to Japan before April 2014, when it ratified the Hague

Convention on the Civil Aspects of International Child Abduction.

Some parents whose children were abducted to Japan after the agreement was signed are finally starting to see some progress in seeking their return, but others, like Conway, remain forgotten.

“There’s only so much you can achieve when it’s pretty much just sanctioned abduction,” he told Stars and Stripes in a series of interviews in September and October. “The numbers aren’t high enough for people to care.”

Japan is known as a “black hole” for

parental child abduction, said Jeffery Morehouse, father to an abducted son,

Atomu, and founder of Bring Abducted Children Home, a U.S.-based nonprofit.

Prior to April 1, 2014, if a Japanese parent living in the United States

returned with their child to Japan, there was very little chance the child

would be returned, or that the other parent would even be granted visitation,

Morehouse said.

Between 1994 and 2014, when the State Department established the Office of Children’s Issues, 416 children were abducted by parents from the U.S. to Japan, according to Bring Abducted Children Home’s website, citing State Department data.

‘Civil legal remedy’

Japan’s western allies began

pressuring it to join the treaty, a Ministry of Foreign Affairs spokesman said

by phone during the first in a series of interviews beginning Sept. 20. The

spokesman declined to say when the first overtures were made.

The Hague Convention provides a

“civil legal remedy” for the return of children who are unjustly removed or

“retained outside their country of habitual residence” in another signatory

country, the U.S. Embassy in Japan website says. The treaty also provides a

framework to “protect legal rights of access and visitation.”

Parents like Conway were not

afforded the benefits of the Hague Convention because their cases occurred

prior to Japan joining the Hague Convention, Morehouse said.

Conway, like the other pre-Hague

parents, was able to apply for access to his children through the Hague

Convention, Conway said. The State Department facilitated his application with

Japan’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs but did little else, he added.

A State Department spokesman declined to comment on

the record for this story.

If an application is accepted, the government of Japan

connects both parents with an outside mediator and local attorneys, but their

involvement stops there, the ministry spokesman said.

Conway was granted Hague access by the ministry on

April 21, 2015, he said. He hired a Japanese attorney and traveled to Japan,

hoping to at least be able to talk to or see his daughters.

He presented the document from the ministry at city hall in Ebina and Zama in Kanagawa prefecture. To his chagrin, they called his ex-wife, Yumika Arima, and asked her if she would provide access to the children, Conway said. She said no.

‘Unenforceable’

Conway’s case is typical, said attorney Jeremy Morley, an expert in international family law based in New York City. “All of those left-behind parents ... are stuck without a remedy, and the Hague Convention has no relevance to their circumstances,” he said.

Morley said their only potential path is through Japanese civil law, but he called that route“totally minimal and meaningless.” Visitation orders are “essentially unenforceable,” he said.

The ministry spokesman admitted as much. “We do our best to realize the visitation or contact, but we don’t have enforceability,” the ministry spokesman said. It’s customary in Japan for some government spokespeople to speak to the media on condition of anonymity.

Conway doesn’t know if the girls would choose an American or Japanese life, but he just wants them to know they were abducted, that they have bank accounts in America, resources and a father who never stopped looking for them, he said.

___________________________________________________________________________________

Matthew M. Burke has been reporting from Okinawa for Stars and Stripes since 2014. The Massachusetts native and UMass Amherst alumnus previously covered Sasebo Naval Base and MarineCorps Air Station Iwakuni, Japan, for the newspaper. His work has also appeared in the Boston Globe, Cape Cod Times, and other publications.

KEISHI KOJA

Keishi Koja is an Okinawa-based reporter/translator who joined Stars and Stripes in August 2022. He studied International Communication at the University of Okinawa and previously worked in education.

Wednesday, August 31, 2022

Child Custody Jurisdiction in India

Jeremy D Morley

Jurisdiction

in India concerning child custody matters is primarily based on the concept of “ordinary

residence.” Section 9 (1) of the Guardian and Wards Act 1890 provides that, “If

the application is with respect to the guardianship of the person of the minor,

it shall be made to the District Court having jurisdiction in the place where

the minor ordinarily resides.” Ordinary residence is not necessarily the same

as habitual residence, but it is based on the original meaning of the term in

English law. Nonetheless, the courts in India have developed their own

jurisprudence concerning its interpretation.

The

leading case is the Supreme Court of India’s ruling in Ruchi Majoo v. Sanjeev

Majoo (2011) 6 SCC 479, which outlines with the simple proposition that

“ordinary residence” means “where the minor ordinarily resides,” but then

provides helpful amplification of that concept.

The key provision in the ruling, explaining the fundamental distinction

between sufficient and insufficient residence, comes in the Court’s analysis of

a prior case, Jagir

Kaur and Anr. v. Jaswant Singh, AIR 1963 SC 1521. The Court in Majoo explained as follows:

The

Court [in Kaur] noticed a near

unanimity of opinion as to what is meant by the use of the word

"resides" appearing in the provision and held that

"resides" implied something more than a flying visit to, or casual stay at a particular place. The legal position was

summed up in the following words:

‘.......Having

regard to the object sought to be achieved, the meaning implicit in the words

used, and the construction placed by decided cases there on, we would define

the word "resides" thus: a person resides in a place if he through

choice makes it his abode permanently or even temporarily; whether a person has

chosen to make a particular place his abode depends upon the facts of each case.....’

"

Thus,

the fundamental distinction is between a mere “flying visit to, or casual stay

at a particular place,” which is insufficient to create ordinary residence and residence

“through choice” to make a place “his abode permanently or even temporarily,”

which may be sufficient. The Court also cited the

case of Kuldip Nayar v. Union of India, AIR 2006 SC 3127, in support of

the proposition that, “residence is a concept that may also be transitory.”

The Indian courts have

further held that an ordinary residence cannot be created by child snatching. A

very recent example is the case of Akhilesh Anjana vs Kavita Anjana (14

March, 2022, Madhya Pradesh High Court), holding that a child who was living

with his father after the father had unilaterally removed him from the

matrimonial home continued to be ordinarily resident in the district in which

he had been living before his father had wrongfully removed him.

In

addition to jurisdiction based on ordinary residence, Indian courts also may

assert child custody jurisdiction on the basis of parens patriae, based

on the traditional duty of the sovereign to protect all who are present in the

country, and on the basis of habeas corpus. Such cases are exceptional

and are primarily founded on the need to provide urgent protection for a child

who is physically present in the district in which the court is located, even

if the child is not ordinarily resident there. These issues arise frequently in

the case of international child abduction to India. In some cases, courts in

India have held that foreign children should be returned to their home country

based on the limited and exceptional jurisdiction founded on parens patriae and

habeas corpus. Merely by way of example, the Supreme Court of India has

most recently ordered the return of an American child to the United States

because of the exceptional circumstances of his abduction. Rohith Thammana Gowda vs The State Of

Karnataka, 29 July, 2022.

However, as

I have often reported, it is critical to note that such returns

are rare and very much the exception rather than the rule.

Monday, July 18, 2022

Honduras: 2022 State Department's Annual Report on International Child Abduction

Country Summary: The Convention has been in force between the United States and Honduras

since 1994. In 2021, Honduras demonstrated a pattern of noncompliance. Specifically, the

Honduran Central Authority regularly failed to fulfill its responsibilities pursuant to the

Convention. Additionally, Honduran law enforcement regularly failed to enforce a return order

rendered by the judicial authority in an abduction case. As a result of this failure, 20 percent of

requests for the return of abducted children under the Convention remained unresolved for more

than 12 months. The sole case affected was unresolved for over one year. Honduras was

previously citied for demonstrating a pattern of non-compliance in the 2015 and 2016 Annual

Reports.

Initial Inquiries: In 2021, the Department received three initial inquiries from parents regarding

possible abductions to Honduras for which no completed applications were submitted to the

Department.

Central Authority: There have been delays in the processing of cases by the Honduran Central

Authority, which contributed to a pattern of non-compliance. In the majority of cases pending in

2021, the Honduran Central Authority failed to take all appropriate steps to facilitate the

institution of judicial proceedings in a timely manner, which resulted in significant delays.

Location: The competent authorities regularly took appropriate steps to locate children after a

Convention application was filed. The average time to locate a child was 42 days.

Judicial Authorities: Delays by the Honduran judicial authorities impacted cases during 2021.

Enforcement: Judicial decisions in Convention cases in Honduras were generally not enforced,

which contributed to a pattern of noncompliance. One case (accounting for 100 percent of the

unresolved cases) has been pending for more than 12 months in which law enforcement failed to

enforce a return order.

Access: In 2021, the U.S. Central Authority had one open access case involving one child under

the Convention in Honduras. This case was opened in 2019 and has been filed with the

Honduran Central Authority. No new cases were filed in 2021. By December 31, 2021, this

case had been resolved.

Department Recommendations: The Department will continue intense engagement with

the Honduran authorities to address issues of concern.

Friday, July 15, 2022

Egypt: 2022 State Department's Annual Report on International Child Abduction

Country Summary: Egypt does not adhere to any protocols with respect to international

parental child abduction. In 2003, the United States and Egypt signed a Memorandum of

Understanding to encourage voluntary resolution of abduction cases and facilitate consular

access to abducted children. In 2021, Egypt continued to demonstrate a pattern of

noncompliance. Specifically, the competent authorities in Egypt persistently failed to work with

the Department of State to resolve abduction cases. As a result of this failure, 85 percent of

requests for the return of abducted children remained unresolved for more than 12 months. On

average, these cases were unresolved for two years. Egypt was previously cited for

demonstrating a pattern of noncompliance in the 2015, 2016, 2019, 2020 and 2021 Annual

Reports.

Initial Inquiries: In 2021, the Department received two initial inquiries from parents regarding

a possible abduction to Egypt for which no additional assistance was requested or necessary

documentation was not received as of December 31, 2021.

Central Authority: In 2021, the competent authorities in Egypt worked closely with the United

States to discuss ways to improve the resolution of pending abduction cases. However, the

competent authorities have failed to resolve cases due to a lack of viable legal options, which

contributed to a pattern of noncompliance.

Location: The Department of State did not request assistance with location from the Egyptian

authorities.

Judicial Authorities: There is no clear legal procedure for addressing international parental

child abduction cases from the United States under Egyptian law and parents face difficulties

attempting to resolve custody disputes in the local courts.

Enforcement: The United States is not aware of any abduction cases in which a judicial order

relating to international parental child abduction needed to be enforced by the Egyptian

authorities.

Department Recommendations: The Department will encourage Egypt to ratify the

Convention and create the legal infrastructure needed for effective implementation of the

Convention.

Thursday, July 14, 2022

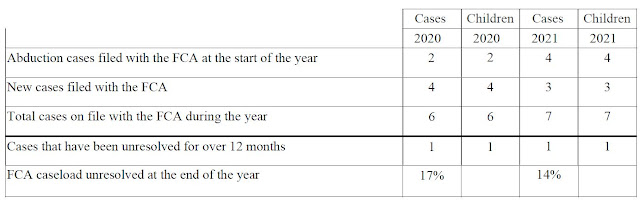

Ecuador: 2022 State Department's Annual Report on International Child Abduction

Country Summary: The Convention has been in force between the United States and Ecuador

since 1992. In 2021, Ecuador continued to demonstrate a pattern of noncompliance.

Specifically, the Ecuadorian authorities persistently failed to take all appropriate measures to

locate children in a timely manner. As a result of this failure, 14 percent of requests for the

return of abducted children under the Convention remained unresolved for more than 12 months.

On average, these cases were unresolved for two years and three months. Ecuador was

previously cited for demonstrating a pattern of noncompliance in the 2015-2021 Annual Reports.

Significant Developments: On July 28, 2021, the National Court of Justice passed a resolution

requiring Ecuador’s courts to use a summary process for Convention cases. This is Ecuador’s

first concrete action to improve Convention compliance since 2015. Shortly after the passage of

the resolution, the Department received the first court-ordered return from Ecuador since 2018.

Additionally, throughout 2021, the National Assembly Special Commission on Children’s Issues

led a review of Ecuador’s Children’s Code. These Children’s Code reforms presented an

opportunity for Ecuador to legislatively implement its obligations under the Convention;

however, the legislation remains stalled in the National Assembly.

Central Authority: The U.S. and the Ecuadorian Central Authorities have a productive

relationship that facilitates the resolution of abduction cases under the Convention.

Location: The competent authorities of Ecuador failed to take appropriate steps to locate

children after a Convention application was filed, which contributed to a pattern of

noncompliance. The average time to locate a child was 9 months and 3 days. As of December

31, 2021, there is one case in which the Ecuadorian authorities remain unable to initially locate

a child (accounting for 100% of the unresolved cases).

Judicial Authorities: Delays by the Ecuadorian judicial authorities impacted cases during

2021.

Enforcement: The United States is not aware of any abduction cases in which a judicial order

relating to international parental child abduction needed to be enforced by the Ecuadorian

authorities.

Department Recommendations: The Department will continue intense engagement with the

Ecuadorian authorities to address issues of concern.

Tuesday, July 12, 2022

Costa Rica: 2022 State Department's Annual Report on International Child Abduction

Country Summary: The Convention has been in force between the United States and Costa

Rica since 2008. In 2021, Costa Rica continued to demonstrate a pattern of noncompliance.

Specifically, the judicial authorities failed to regularly implement and comply with the

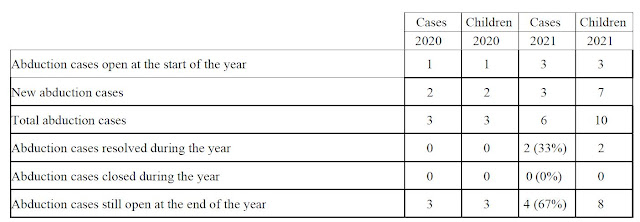

provisions of the Convention. As a result of this failure, 67 percent of requests for the return of

abducted children under the Convention remained unresolved for more than 12 months. Costa

Rica was previously cited for demonstrating a pattern of noncompliance in the 2011-2016, 2020,

and 2021 Annual Reports.

Initial Inquiries: In 2021, the Department received two initial inquiries from parents regarding

a possible abduction to Costa Rica for which no completed applications were submitted to the

Department.

Significant developments: Costa Rica’s Supreme Court, with the support of the Department

and U.S. Embassy San Jose, successfully hosted a series of virtual seminars on Convention best

practices. The seminars brought together Costa Rican Supreme Court judges, Department

representatives, as well as legal experts and judges from Costa Rica, Uruguay, Argentina,

Mexico, Spain, Canada, and the United States. Presenters offered legal analyses to raise

awareness of the Convention and its core governing principles, and shared best practices for

implementing Convention protocols. In September 2021, the Department organized an

International Visitor Leadership Program (IVLP) for members of Costa Rica’s judicial and legal

community. The IVLP focused on how Convention issues are approached in the U.S. legal

system.

Central Authority: The U.S. and the Costa Rican Central Authorities have a productive

relationship that facilitates the resolution of abduction cases under the Convention.

Location: The competent authorities regularly took appropriate steps to locate children after a

Convention application was filed. On average, it took less than one month to locate a child. As

of December 31, 2021, there was one case in which the Costa Rican authorities remained unable

to locate one child, representing 50 percent of unresolved cases for 2021.

Judicial Authorities: There were serious delays by the Costa Rican judicial authorities in

deciding Convention cases. As a result of these delays, cases have been pending with the

judiciary for over one year, contributing to a pattern of noncompliance.

Enforcement: The United States is not aware of any abduction cases in which a judicial order

relating to international parental child abduction needed to be enforced by the Costa Rican

authorities.

Department Recommendations: The Department will continue intense engagement with Costa

Rican authorities to address issues of concern.

Monday, July 11, 2022

Brazil: 2022 State Department's Annual Report on International Child Abduction

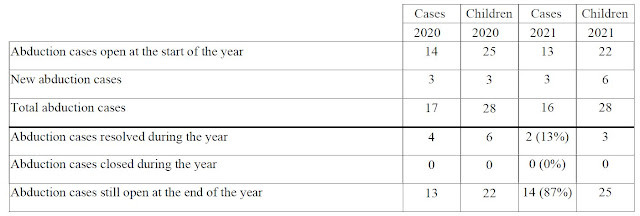

Country Summary: The Convention has been in force between the United States and Brazil since 2003. In 2021, Brazil continued to demonstrate a pattern of noncompliance. Specifically, judicial authorities continued to fail to regularly implement and comply with the provisions of the Convention. Additionally, the competent authorities continued to fail to take appropriate steps to locate children in an abduction case, contributing to Brazil’s persistent failure to implement and abide by the provisions of the Convention. Brazil was previously cited for demonstrating a pattern of noncompliance in the 2006-2021 Annual Reports.

Initial Inquiries: In 2021, the Department received four initial inquiries from parents regarding possible abductions to Brazil for which no completed applications were submitted to the Department.

Significant Developments: In 2021, Brazil named six new members to the International Hague Network of Judges, expanding from a previous single active Network judge. Additionally, Brazil’s Federal Justice Council published a manual to guide federal judges when hearing Convention cases.

The Department has cited Brazil for demonstrating a pattern of noncompliance with the Convention for 17 consecutive years. However, by the end of 2021, a significant number of abduction cases were resolved, and less than 30 percent of cases remained unresolved for more than 12 months. While these resolutions are encouraging, other cases continue to experience lengthy judicial delays, contributing to Brazil’s persistent failure to implement and abide by the provisions of the Convention. The Department continues to call on Brazil to expedite the resolution of Convention cases.

Central Authority: The U.S. and Brazilian Central Authorities have a strong and productive relationship that facilitates the resolution of abduction cases under the Convention.

Thursday, July 07, 2022

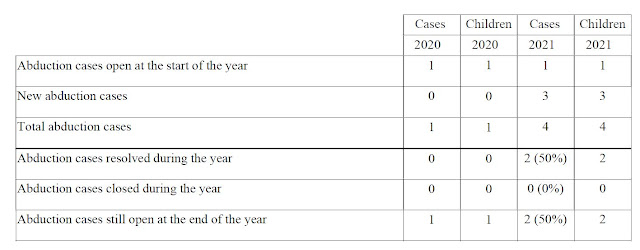

Belize: 2022 State Department's Annual Report on International Child Abduction

Country Summary: The Convention has been in force between the United States and Belize

since 1989. In 2021, Belize demonstrated a pattern of noncompliance. Specifically, the judicial

authorities failed to regularly implement and comply with the provisions of the Convention. As

a result of this, 50 percent of requests for the return of abducted children under the Convention

remained unresolved for more than 12 months.

Central Authority: The United States and the Belizean Central Authorities have a strong and

productive relationship that facilitates the resolution of abduction cases under the Convention.

Location: The competent authorities took appropriate steps to locate children after a

Convention application was filed. The average time to locate a child was 31 days. As of

December 31, 2021, there were no cases where the Belizean authorities remained unable to

initially locate a child.

Judicial Authorities: Delays by the Belizean judicial authorities impacted cases during 2021.

As a result of these delays, one case has been pending with the judiciary for over two years,

contributing to a pattern of noncompliance.

Enforcement: The United States is not aware of any abduction cases in which a judicial order

relating to international parental child abduction needed to be enforced by the Belizean

authorities.

Department Recommendations: The Department will continue intense engagement with the

Belizean authorities to address issues of concern.

Wednesday, July 06, 2022

Austria: 2022 State Department's Annual Report on International Child Abduction

Country Summary: The Convention has been in force between the United States and Austria

since 1988. In 2021, Austria demonstrated a pattern of noncompliance. Specifically, the judicial

authorities failed to regularly implement and comply with the provisions of the Convention, and

law enforcement regularly failed to enforce return orders rendered by the judicial authority in

abduction cases. As a result of this failure, 33 percent of requests for the return of abducted

children under the Convention remained unresolved for more than 12 months. On average, these

cases were unresolved for two years and three months.

Central Authority: While the U.S. and the Austrian Central Authorities have a cooperative

relationship, delays in communication about actions to resolve Convention cases are an area of

continuing concern.

Voluntary Resolution: The Convention states that central authorities “shall take all appropriate

measures to secure the voluntary return of the child or to bring about an amicable resolution of

the issues.” In 2021, one abduction case was resolved through voluntary means.

Location: The competent authorities took appropriate steps to locate a child after a Convention

application was filed in 2021. It took eight days to locate this child. The competent authorities of

Austria failed to take appropriate and expeditious steps to locate another child after an

enforcement order was issued for the return of the child. It took 53 days to locate this child,

which led to delays in the enforcement and return of the child.

Judicial Authorities: Judicial authorities rendered decisions that were not consistently in

accordance with the Convention and there were delays in judicial authorities deciding on a case.

In one case, after multiple appeals, the Austrian Supreme Court ordered a lower court to enforce

a return order; however, the lower court instead dismissed the Convention case and made a

custody decision. While the lower court’s order was eventually overturned, these problems in

the performance of judicial authorities contributed to a pattern of noncompliance.

Enforcement: While the Supreme Court of Austria ordered the enforcement of a Convention

return order in 2021, the lower court and Austrian authorities charged with the enforcement

responsibility declined to enforce the order, which contributed to a pattern of noncompliance.

After the Supreme Court overruled the lower court’s dismissal of its return order, enforcement

actions were initiated in December 2021; the child was returned to the United States in January

2022. There was one case (one hundred percent of the unresolved cases) that was pending for

more than 12 months in which the competent authorities and law enforcement failed to enforce

a return order.

Department Recommendations: The Department will continue engagement with the Austrian

authorities to address issues of concern.

Monday, July 04, 2022

Argentina: 2022 State Department's Annual Report on International Child Abduction

Country Summary: The Convention has been in force between the United States and

Argentina since 1991. In 2021, Argentina continued to demonstrate a pattern of noncompliance.

Specifically, the Argentine judicial authorities failed to regularly implement and comply with the

provisions of the Convention. As a result of this failure, 50 percent of requests for the return of

abducted children under the Convention remained unresolved for more than 12 months. The sole

abduction case still open at the end of 2021 has been unresolved for 11 years and six months.

Argentina was previously cited for demonstrating a pattern of noncompliance in the 2015-2021

Annual Reports.

Significant Developments: Delays persisted within the Argentine judiciary in 2021,

contributing to a pattern of noncompliance. The sole abduction case still open at the end of 2021

has been unresolved in the Argentine judiciary for 11 years and six months, the Department’s

longest-running open unresolved abduction case in the world. The other abduction case open

during 2021 resolved this year, after being unresolved for just under two years, mostly due to

delays in the judiciary. Argentina’s legislature failed to enact national procedural legislation

designed to address Argentina’s judicial delays in early 2021 after interlocutors reported it lost

“parliamentary status,” and officials did not reintroduce a draft bill for the remainder of the year.

Central Authority: The U.S. and Argentine Central Authorities have a productive relationship.

Location: The Department of State did not request assistance with location from the Argentine

authorities.

Judicial Authorities: There were serious delays by the Argentine judicial authorities in

deciding Convention cases. As a result of these delays, cases may be pending with the judiciary

for over one year, contributing to a pattern of noncompliance.

Enforcement: In one case unresolved for almost 12 years, Argentine courts have suspended a

return order. Additionally, Argentina’s legal system allows multiple appeals both on the merits

of the decision and on the manner in which the decisions are enforced, thereby creating

excessive delays which contribute to a pattern of noncompliance.

Access: In 2021, the U.S. Central Authority had one open access case involving one child under

the Convention in Argentina. This was opened in 2018. This case has been filed with the

Argentine Central Authority. No new cases were filed in 2021. By December 31, 2021, this case

remained open. This case has been pending with the Argentine authorities for more than 12

months.

Department Recommendations: The Department will continue intense engagement with

Argentine authorities to address issues of concern.

Monday, March 07, 2022

PREVENTING CHILD ABDUCTION TO LEBANON

by Jeremy D. Morley

Lebanon is, in my opinion, a proven safe haven for international parental child abduction. I testified to this effect last month in great detail in a case in Texas.

My

credentials include extensive research concerning Lebanese family law,

consultations with numerous clients, and often with Lebanese counsel,

concerning abductions and potential abductions to Lebanon, and my hosting of a

meeting about Lebanese family law. in New York with three Lebanese judges (one

from a Christian court, one from a Sharia court and one from a civil court) as

well as a top Lebanese family lawyer.

Lebanon

has failed and refused to adopt the Hague Abduction Convention. It has a religious-based

judicial system in the sphere of family law matters. It does not have one civil

code regulating personal status matters. There are 15 separate personal status

laws for the country’s different recognized religious communities, twelve of

which are Christian and four are Muslim, with the remaining courts and laws

being for Druze and Jews. Each of these laws are administered by separate

religious courts. It is often extremely difficult to enforce custody orders in

Lebanon and it is relatively simple for parents to frustrate the process for

extended periods of time by moving to other locations in Lebanon or by

initiating new civil or criminal proceedings within Lebanon.

Given

the current overwhelming challenges that Lebanon faces with terrorism,

corruption and a collapsed economy, it is most unlikely that the extreme

difficulties faced by left-behind parents in trying to secure the return of

children who have been abducted to Lebanon will be ameliorated in the

foreseeable future.

Wednesday, February 23, 2022

INTERIM MAINTENANCE IN HIGH-NET-WORTH CASE IN ENGLAND, DESPITE NEW YORK PRENUPTIAL AGREEMENT

By Jeremy D. Morley*

High-net-worth divorce cases in England can be both unpredictable and extremely expensive, even when the parties have signed a well-drafted, thoroughly reviewed and subsequently modified New York prenuptial agreement containing substantial provisions for the lesser wealthy spouse. A case on point is Collardeau-Fuchs v. Fuchs, [2022] EWFC 6 (21 February 2022).

The

parties had signed a New York prenuptial agreement, in which the husband had

disclosed a net worth of more than £1 billion, and the wife a net worth of about

£4 million. They had then signed a modification of the prenuptial agreement

during the marriage. Fortunately for the wife, she was able to bring her divorce

case in London, where the family owned an extremely valuable home. The family

also owned extremely valuable residential properties in New York, France and

other locations.

An

interim decision in the case was rendered a few days ago, solely on the

question of the amount of interim maintenance to be paid by the husband,

pending the final resolution of the case. It was only an 8-year marriage,

although in England it would be deemed a 12-year relationship since the parties

had cohabited for 4 years prior to the marriage (or only for 2 years according

to the husband). The length of the

relationship is a factor of far greater significance in England than in New

York.

The

prenuptial agreement, as modified, provided that the wife would receive a lump-sum

payment upon a divorce of £23.5 million plus 18 years of rent-free

accommodation at the family home in West London, valued at £30 million.

Under

English law, the prenuptial agreement could not modify or limit the duty of the

English court to provide for interim maintenance to parties in “need.” New York

does not necessarily so provide. The decision of the English court by the Hon.

Mr. Justice Mostyn -- an English High Court judge who had himself once achieved

fame as a barrister with the nickname of “Mr Payout” because of the enormous

sums he had won for divorcees – concerned nothing more than the extremely

preliminary issue of interim maintenance.

The

English court determined that, during the pendency of the divorce case, the

husband must pay to the wife sufficient sums as would meet her “reasonable

needs.” It held that English law required that the term “reasonable needs” must

be interpreted in light of the standards enjoyed by the parties during the

marriage. Since the reality was that “the husband and wife in this case belong

to a tiny percentage of the world population who have control and management

and entitlement to huge sums of money,” the wife’s “reasonable needs” must be

considered “according to the standards of the ultra rich.” The court insisted

that it had a duty to “avoid the risk of confining [the needs of the wife] by

the application of scales that would seem generous to ordinary people.”

The

court found that the portion of the parties’ annual living costs that was

attributable to the wife, for the last full year before the parties separated,

was approximately £855,000.00 ($1,368,000.00), of which about 55% (£475,000.00)

was for (obviously lavish) vacations. This sum did not include the cost of

staff for the West London house (two chefs, a house manager, 2 or 3

housekeepers, a launderer, and numerous contractors such as gardeners, pool

maintenance builders, plumbers, electricians, and handymen) solely, as well as

other “Overheads.”

Accordingly,

the court ordered the husband to pay the sum of £855,000.00

a year to the wife on an interim basis until the conclusion of the case, plus £2.78

million a year for staff and overhead, for a grand total of £3.635 million (almost

$5 million) per annum.

The

court also ordered the husband to pay all of the wife’s legal fees, both past

due and those yet to be incurred. Judge Mostyn explained that, although the

litigation was only “at a relatively early stage,” the parties had nonetheless already

incurred considerable legal costs which amounted to about £917,000.00, with

another £288,700.00 anticipated through the end of the next month, for an

interim total of £1,205,000.00 ($1.64 million).

Meanwhile,

the very much larger issue of the full effect of the prenuptial agreement in

England remains to be determined. In this regard, the contrast between New York

and English law remains extreme. It is clear the public policy of the New York courts

to encourage marrying couples to create certainty about their financial

arrangements by entering into prenuptial agreements. The New York courts will

enforce the terms of a well-drafted prenuptial agreement upon a divorce absent

proof of unconscionability or extreme unfairness or duress, or other unusual

circumstances. But courts in England are far more circumspect in their enforcement

of such agreements, even when there has been full financial disclosure and

independent legal representation. English judges remain particularly protective

of the rights of less wealthy spouses and the need to consider “fairness” in

determining whether to apply or modify the terms of a prenuptial agreement. The

wife in the just-reported case seems to have been extremely fortunate, or

extremely wise or strategic, to have been able to bring her case in London, and

not in New York.

_____________________

* Jeremy D. Morley is a

New York lawyer who collaborates with counsel in England and other

jurisdictions in handling international prenuptial agreements. He may be

reached at www.international-divorce.com

and www.internationalprenuptials.com

Monday, February 14, 2022

FINANCIAL RESTITUTION AGAINST INTERNATIONAL PARENTAL CHILD KIDNAPPERS

U.S. law allows a left-behind parent whose child has been abducted to the United States to compel the abducting parent to repay all of the fees and expenses incurred in seeking the child's return. 22 U.S.C. §9007(b)(3). But there is no similar provision that clearly entitles a left-behind parent whose child has been abducted out of the United States to seek reimbursement from the abductor of the fees and expenses incurred in seeking the child's return to the United States.

There

is appears to be a split between the Ninth and Tenth Circuits as to whether

federal legislation that authorizes an award of restitution to a victim of criminal

offense can be used to recoup a left-behind’s parent’s legal expenses in cases

of international parental child abduction once the abductor has been found

guilty of international parental child kidnapping pursuant to the International

Parental Kidnapping Crime Act (the “IPKCA”) 18 U.S.C. §1204.

The

Victim and Witness Protection Act of 1982 authorizes a federal district court

to sentence a criminal defendant to pay restitution to a

victim of the offense to the extent of “expenses related to participation in

the investigation or prosecution of the offense.” 18 U.S.C. §3663(b)(4).

In

U.S. v. Cummings, 281 F.3d 1046 (9th Cir. 2002), the

defendant father was successfully prosecuted under the IPKCA for having abducted

his children from their home in the State of Washington to Germany. The left

behind mother brought a return action against the father in Germany under the

Hague Abduction Convention and an action in the State of Washington for

contempt of court for his violation of a custody order. The father was

sentenced to a term in jail and was required to pay the mother’s legal fees and

expenses in the two civil actions. The Ninth Circuit upheld the restitution

award, holding that the mother’s civil cases were not “wholly separate” from

the government’s prosecution of the father. This was supported by the fact

that, by initiating a case under the Hague Convention, the mother had followed

the procedure specifically described in the IPKCA as the preferred “option of

first choice” for a left-behind parent.

More

recently, however, the Tenth Circuit held in U.S. v. Mobley, 971 F.3d 1187

(10th Cir. 2020) that it would not follow Cummings. In Mobley, the

government prosecuted a mother under the IPKCA for her abduction of her children

from their home in Kansas to Russia. Once she was in Russia, she had filed there

for divorce and custody in Russia. The left-behind father had then sued for

divorce and custody in Kansas. The Russia court had given custody to the

mother, and the Kansas Court given custody to the father. The district court found

the mother guilty under the IPKCA and ordered restitution to the father of the

legal fees and expenses that he had incurred in connection with the two civil

cases.

On

appeal, the Tenth Circuit overturned the restitution award. It held that §3663 is

not satisfied by evidence that the expenses were incurred in proceedings that

were merely “related to” the criminal offence. Instead, the expenses must be “related

to participation in the investigation or prosecution of the offense or attendance

at proceedings related to the offense.” It held that the terms “investigation”,

“prosecution” and “proceedings” are limited to the government's investigation,

the government's criminal prosecution, and the criminal proceedings, in

accordance with the ruling of the U.S. Supreme Court in Lagos vs. U.S.,

138 S. Ct. 1684 (2018). There was no evidence that the government had directed

or sanctioned the father’s civil proceedings, and the mother's attempts to

secure children’s return “did not assist the government in its investigation or

of prosecution of the mother.”

It

remains to be seen whether Mobley will, in future cases, be successfully

distinguished on its facts. Specifically, it is possible that proof could be

elicited that the litigation efforts of a left-behind parent assisted the

governor's prosecution of an international parental kidnapping case. In such a

case, a restitution award might still be deemed appropriate. Even then,

restitution would be restricted to those few cases in which an abductor is

prosecuted under the IPKCA. Of course, recovery in any such case would be

extremely remote.

Friday, February 11, 2022

Hague Abduction Cases: Left-behind Parents, Lawyers & Judges Must Understand How Central Authorities’ Roles Vary Dramatically between Countries

The Hague Abduction Convention requires each treaty party to establish a Central Authority to provide assistance in both “outgoing” cases in which a child is taken away from a country and “incoming” cases in which a child has been brought into the country. The Convention leaves it up to each country to decide how the Central Authority will operate.

In some countries the Central

Authority exercises a leading role in handling cases under the Convention. In

other countries, such as the United States, the Central Authority’s role is

extremely limited. This discrepancy is often unrecognised, and it may lead to confusion

and even serious error.

In Australia,

the Central Authority is a department within the Attorney-General's Department

of the Australian Government. There are also separate Central Authorities for

each Australian state or territory. In most Hague Convention cases in

Australia, the appropriate Central Authority itself initiates judicial

proceedings in the Australian courts for the return of children allegedly

abducted to Australia. Indeed, the Central Authority is the plaintiff in any such

case and the Central Authority lawyers do not take instructions concerning the

conduct of such cases directly from the left-behind parent, who is not even a

party to the legal proceedings. Left-behind parents may, in the alternative,

start a case in their own name but this is unusual and perhaps ill-advised.

Similarly,

the Central Authorities in Germany and New Zealand take on a substantial role in

initiating judicial proceedings under the Convention.

However,

cases in the United States are handled in a completely different way. The Central Authority in the United

States is the State Department's Office of Children's Issues in the Bureau of

Consular Affairs. It does not initiate litigation in any Hague Convention case

and it has no power to do so. It has no responsibility or function to bring any

cases under the Convention or to be involved in any significant way in any

Hague Convention judicial proceeding. The Office of Children’s Issues has no

judicial function whatsoever. It has no authority to secure a child’s return

pursuant to the Convention. It is exclusively the responsibility of the

left-behind parent to retain counsel and to commence a court case in the United

States to seek an order that an abducted child must be returned.

Upon receipt of an application that

is made by a left-behind parent under the Convention, whether the application

is submitted by a foreign Central Authority or even if it is submitted directly

by the left-behind parent, the United States Central Authority may assist with

locating the child, and it will send a simple letter to the other parent suggesting

mediation or a voluntary return, but it will certainly not file a case in court

for the return of the child.

Unfortunately, foreign Central

Authorities may not fully understand that the U.S. State Department does not

have any proactive role in litigating Hague Convention cases and they may not

inform left-behind parents that they must start their own cases in the United

States.

The fact that this critical

distinction between Central Authorities that handle the Hague Convention case

and those that do not is often misunderstood is even reflected in the current

website of the Australian Central Authority, which includes advice on “International parental child

abduction” that includes

a flowchart of the “Application process for return of an abducted child to Australia.”

The flowchart states that the steps to recover a child who has been abducted

from Australia are as follows:

·

The

first step is “Application received by Australian Central Authority (ACA).

·

The

second step is “ACA assesses application against the Hague Convention.”

·

The

third step, if there is a positive assessment, is “Application accepted by ACA,

transferred to relevant CA in other country.”

·

The

fourth and critical step, according to the flowchart, is:

“Overseas

central authority takes appropriate action which may include mediation, seeking

a voluntary return, or filing in court for the return of the child.”

Unfortunately,

that advice is completely incorrect and misleading with respect to abductions

to countries such as the United States. In particular, the U.S. Central

Authority does not file a court case for the return of the child. To make

matters worse, the Australian website does not warn left-behind parents that it

is their sole responsibility to start the Hague case in the United States, and that

the U.S. Central Authority will not handle it.

Similar confusion is shown in a case

that is currently before the courts in New York. The Central Authority in

Luxembourg is the State Prosecutor’s Office (the Parquet Generale Cite

Judiciare). As is the case with Australia, that office is responsible for

prosecuting incoming abduction cases in Luxembourg and its role is expansive

and proactive. In the pending matter in New York, the Luxembourg Central

Authority submitted to the U.S. Central Authority a formal referral of an

application for a child’s return to Luxembourg, in which it requests the U.S.

State Department to “take all the measures contained in article 12 of the above-mentioned

Convention for the immediate return of the child to Luxembourg.” As stated above,

the State Department does not take any such action and cannot do so. Is it any

wonder that a left-behind parent would expect that the U.S. State Department is

handling the matter?

In my extensive experience, left-behind

parents often think that, merely because they have submitted an application for

their child’s return from the United States under the Convention, they have

“started a Hague case.” Nothing could be further from the truth. Central

Authorities must ensure at a minimum that they do not provide incorrect

information to their citizens. Nor should they suggest that left-behind parents

should seek legal advice from the U.S. Central Authority, which cannot provide

any such advice. In addition, I must reluctantly state that many of my clients

have informed me that they have received incorrect or incomplete advice from

the U.S. Central Authority.

Left-behind parents must be warned

that, if they do not commence a case in a U.S. court within one year of the

date of the wrongful removal or retention, the abductor will be able to take

advantage of the provision in Article 12 of the Convention that the court need

not order the return of a child who has become settled in the new environment. The

International Child Abduction Remedies Act provides that “the term ‘commencement

of proceedings’, as used in Article 12 of the Convention, means, with

respect to the return of a child located in the United States, the filing

of a petition in accordance with subsection (b) of this section.” 42

U.S.C. § 11603(f)(3). Accordingly, the one-year period is not tolled by reason

of the mere filing of a Hague application even if the left-behind parent

believed that filing the application was sufficient or believed that the U.S.

State Department was handling the case. Monzon

v. De La Roca, 910 F.3d 92 (3d Cir. 2018).

The submission of an application to the Office of Children’s

Issues does not constitute the initiation of judicial proceedings, does not

stop the clock for purposes of the “one year and settled” exception to the

Convention, and does not require the alleged abductor to take or not to take

any action. The Office does not appoint attorneys for left-behind parents, and

it does not file return petitions with the courts. Unlike several other

countries, and notwithstanding the advice that may be provided by some Central

Authorities, the responsibility for starting a Hague case in an appropriate

court in the United States rests exclusively with the

left-behind parent.