Kyodo News International

March 18, 2014

More than 40 Japanese lawmakers set up a group Tuesday with an

aim to enact legislation to ensure visitations between children and

their parents separated due to divorce or marital disputes in Japan.

The lawmakers from both ruling and opposition parties will strive

to prevent severance of the parent-child relationship for the child's

best interest, as more than 150,000 children in Japan every year are

estimated to lose contact with noncustodial parents following divorce.

Japan adopts the sole custody system and the country's courts tend

to award mothers custody. It is not unusual for children to stop seeing

their fathers after their parents break up.

At the first

meeting of the parliamentarians' group, Minoru Kiuchi, a ruling Liberal

Democratic Party member of the House of Representatives, said that not

being able to meet with their own child would "violate the human rights

of fathers."

Kiuchi referred to his own experience of being

temporarily separated from his children in the past due to a dispute

with his wife.

A group of parents separated from their

children urged the lawmakers at the meeting to increase the frequency of

visitations, ban parental child abductions and oblige couples to work

out a joint parenting plan for their children when they get divorced.

According to a government survey on visitations in fiscal 2011,

23.4 percent of 1,332 single mothers and 16.3 percent of 417 single

fathers said they have agreed on a scheme of exchanges between children

and their separated parents.

As for the frequency of

visitations, 36.5 percent of 603 single mothers and 42.3 percent of 225

single fathers said their children have met with nonresident parents

more than once a month.

LDP lower house member Hiroshi Hase,

who heads the secretariat of the lawmakers' group, said that members

will meet once a month and conduct fact-finding surveys before starting

work to craft a new law.

The members will also promote

awareness among the general public that it will be desirable for

children to maintain access to both parents, he said.

http://www.globalpost.com/dispatch/news/kyodo-news-international/140318/lawmakers-launch-group-ensure-visitations-after-divorc

Wednesday, March 19, 2014

Wednesday, March 05, 2014

Supreme Court New Hague Abduction Convention Ruling

The U.S. Supreme Court has today, in

Lozano v. Montoya Alvarez, upheld the Second Circuit ruling that the one year

period in the “one year and settled” exception to the Hague Abduction

Convention is not subject to equitable tolling.

The decision is not surprising since that is what the treaty provides and the American equitable tolling gloss was not contemplated in the Hague drafting process and has only been applied in this country.

What is refreshing in the opinion of Justice Thomas is his use of international authority as the key basis for the decision.

Justice Thomas relied significantly on case law from England, Canada, New Zealand and Hong Kong in reaching the conclusion that the U.S. reliance on equitable tolling was out of the international mainstream and inappropriate.

Now, if only the Supreme Court would bring the U.S.’s crazily conflicting and confusing interpretations of habitual residence in Hague cases into the international mainstream!

Monday, March 03, 2014

Russia to establish special courts for international kidnapping cases

MOSCOW, March 3 (RAPSI) –

Russia will establish special courts to adjudicate cases involving

international kidnapping cases, Deputy Minister for Education and

Science Veneiamin Kaganov told RIA Novosti Monday.

In 2011, Russia joined the International Convention on the Civil Aspects of International Child Abduction, which aims to facilitate the immediate retrieval of children unlawfully transported to any of the 87 member states of the Convention.

Earlier in February, the Russian State Duma passed a bill establishing a review procedure for cases concerning the return of children, and granting custody rights.

Russia has seen a number of international custody rows, including several with France and Finland.

Irina Belenkaya, a Russian national accused of kidnapping her daughter and orchestrating an attack on her ex-husband Andre, received a two-year suspended sentence in a French court in 2012. The couple has been embroiled in a bitter custody battle resulting in their daughter Elise being "kidnapped" back and forth three times in 2007-2009. Andre was awarded custody by a French court after their divorce in 2007.

Several similar cases have arisen in Finland following the introduction of a 2008 law stating that children should be taken from their families immediately, where mistreatment is suspected.

Rimma Salonen's case was one of the first public scandals to emerge involving Russian-Finnish children.

After Salonen brought her son Anton back to Russia, he was again returned to Finland in the trunk of a diplomat's car three years ago by his father Paavo Salonen and diplomat Simo Pietilainen, who have escaped criminal liability in Finland. Rimma Salonen was deprived of her parental rights by a Finnish court and received a suspended sentence for abducting her son after her divorce from Paavo.

http://rapsinews.com/judicial_news/20140303/270853120.html

In 2011, Russia joined the International Convention on the Civil Aspects of International Child Abduction, which aims to facilitate the immediate retrieval of children unlawfully transported to any of the 87 member states of the Convention.

Earlier in February, the Russian State Duma passed a bill establishing a review procedure for cases concerning the return of children, and granting custody rights.

Russia has seen a number of international custody rows, including several with France and Finland.

Irina Belenkaya, a Russian national accused of kidnapping her daughter and orchestrating an attack on her ex-husband Andre, received a two-year suspended sentence in a French court in 2012. The couple has been embroiled in a bitter custody battle resulting in their daughter Elise being "kidnapped" back and forth three times in 2007-2009. Andre was awarded custody by a French court after their divorce in 2007.

Several similar cases have arisen in Finland following the introduction of a 2008 law stating that children should be taken from their families immediately, where mistreatment is suspected.

Rimma Salonen's case was one of the first public scandals to emerge involving Russian-Finnish children.

After Salonen brought her son Anton back to Russia, he was again returned to Finland in the trunk of a diplomat's car three years ago by his father Paavo Salonen and diplomat Simo Pietilainen, who have escaped criminal liability in Finland. Rimma Salonen was deprived of her parental rights by a Finnish court and received a suspended sentence for abducting her son after her divorce from Paavo.

http://rapsinews.com/judicial_news/20140303/270853120.html

Friday, February 28, 2014

English Prenuptial Plan Ill-Considered

I believe that the U.K. Law Commission’s

hot-off-the-press proposal about prenuptial agreements in England and Wales is somewhat

ill-considered.

The reason that parties who marry want prenuptial

agreements is to create security as to the financial terms of their future

relationship and to avoid the potential expense, intrusiveness and uncertainty

of litigation concerning the financial aspects of their potential divorce. That

is particularly so in England, whose divorce courts are renowned for applying

the loose term of “fairness” in unpredictable and expansive ways.

Unfortunately, while the Law Commission has proposed

that prenuptial agreements will be enforceable in England and Wales, it has

also proposed an exception insofar as such agreements do not satisfy the

“financial needs” of the parties. The exception might appear at first blush to

be innocuous and sensible. In fact, however, it would create a gaping chasm of

uncertainty that would undermine the basic goals of predictability, simplicity

and autonomy. The proposed exception is so broad and its terms are so vague

that no one will really know how it might be applied to the facts of any

particular case. The Law Commission proposes some kind of non-binding

“guidance” about “needs” to assist decision-makers in their task of interpreting

that term in specific cases, which serves to underscore the fact that there

will be substantial uncertainty under its proposal as to what the exception

will include and how it will be applied.

The result may well be as follows:

a. Prenuptial

agreements will be far more expensive than would otherwise be the case because

lawyers will need to analyze the parties’ current and prospective circumstances

in order to be able to provide any kind of useful advice, and will need to

draft contracts with loose terms and enormous disclaimers in order to handle

such uncertainty.

b. Prenuptial

agreements will be of limited value. Current English law provides that the

financial needs of the parties are the basis upon which the English courts

decide the financial side of divorce cases in England unless the parties have

more financial resources than is required to cover all of their “needs.” Since prenuptial agreements cannot be less

generous than the courts would apply in a needs case there may be little or no

point in going through the trouble and expense of entering into any such

contract.

c. Prenuptial

agreements will probably have to include provisions that are even more generous

than current “needs” might suggest. It is impossible to guess the financial

circumstances that parties will be in at the time of a potential divorce years

down the line. Therefore it will be impossible to come up with specific

financial terms that will satisfy a test which is based on future

circumstances. Alternatively, prenuptial agreements will require broadly

written exceptions that will be entirely unpredictable as to their potential

application.

d. The role of the

courts in the financial aspect of divorces will continue to be vast, intrusive

and expensive, since unhappy litigants will always claim that their needs have

not been met.

e. There will continue

to be a substantial incentive for forum shopping, since courts in most of the

rest of the world may well enforce prenuptial agreements far more liberally,

reliably and usefully than the courts in English and Wales.

The Law Commission’s fundamental mistake stems from

the fact that it does not trust the parties to make sensible agreements. It

believes that the judiciary should continue to act in a quasi-parental capacity

to oversee the decisions made by adults who purposefully, deliberately and

freely enter into contracts that will define the financial terms of their

relationship.

Quite appropriately the Commission’s proposal

contains substantial provisions to ensure that any prenuptial agreement must be

entered into with the parties’ eyes wide open. Thus, it proposes that there

should be a gap of 28 days between the execution of the agreement and the date

of the marriage; that disclosure of “material circumstances” should be required

(although this term is hardly defined in the proposal); and that the parties

should have legal advice (presumably independent advice) before signing the

contract. However, the Commission then proceeds to carve out the mammoth

exception of “financial needs” in order to make sure that consenting adults do

not sign silly agreements.

It is important to point out that the exception would

not be limited, as many other jurisdictions provide, to periodic spousal

support. It would also extend to the assets

of the parties, and unlike most other jurisdictions that will include

pre-marital as well as post-marital assets.

I am not usually a flag-waver for the jurisdiction

in which I practice but, in the case of prenuptial agreements, I think that New

York has got it about right. Our statute provides, in essence, that

properly-executed prenuptial agreements are binding absent “unconscionability,”

which requires proof of inequality that is “so strong and manifest as to shock

the conscience and confound the judgment of any [person] of common sense.” A

lower standard is reserved for terms that limit spousal maintenance, which will

be upheld if “fair and reasonable at the time of the making of the agreement

and … not unconscionable at the time of the [divorce].” While mere fairness is

required, it is measured at the time the contract is made so that the

circumstances then in existence can be sensibly evaluated at that time. In

addition, unlike England, spousal support is always periodic in New York and is

invariably time limited at the outset. There is a clear and very strong public

policy in New York favoring the right of parties to set their own terms when

they marry but there will be greater scrutiny if there has not been adequate

disclosure of financial matters before marriage or independent legal

representation or a reasonable gap between the presentation of a prenuptial

agreement, its execution and the parties’ marriage. The result is that New York

prenuptial agreements are relatively easy to draft, relatively inexpensive, and

extremely useful since they are invariably upheld if properly drafted. We are

able to advise clients sensibly and predictably.

In sharp contrast, the U.K. Law Commission proposes

to create a prenuptial regime that retains an excessively paternalistic role

for the English courts that is likely to lead to excessive litigation,

complicated agreements and unpredictable results.

Friday, February 21, 2014

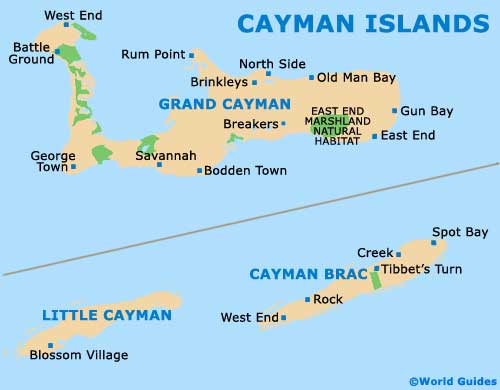

Cayman Islands: Family court rulings made public

Family court rulings made public

Local

courts buck long trend of secrecy

By:

Brent Fuller

| brent@cfp.ky

20

February, 2014

To protect the identities of the parties involved, the court’s judgment contains only initials in relation to the individuals being discussed, not their full names. Also, Courts Administrator Kevin McCormac said it remains in the discretion of the presiding judge whether the ruling on a particular case is put into the public domain.

“In the majority of family proceedings, the decisions are purely about the private affairs of the parties involved,” Mr. McCormac said. “Occasionally, there will be a judgment that is of wider interest.”

So far, the courts have released five such cases believed to have some broader public interest from the Grand Court’s Family Court Division.

The latest release involves a Jan. 15, 2014 judgment on a Cayman Islands residency case where the right of two children to remain in the islands was being reviewed, following the death of their father – a permanent resident of independent means. The residency status of the children was granted as dependents of their permanent resident father, who died late last year.

“There is a live issue as to whether their right to residency had ceased upon [their father’s] passing and uncertainty as to their right to continue residing in the Cayman Islands,” the judgment written by Grand Court Justice Richard Williams indicated.

In addition to deciding whether the children could continue to reside in the Cayman Islands, there was an ongoing issue as to legal guardianship and who might be responsible for their care if they could not remain here.

In the end, the judge ruled that the children should be made temporary wards of the court and placed in the interim care of relatives who reside in Florida. However, that decision was based largely on what the court considered best for the children at the time, rather than a decision based on their immigration status in the Cayman Islands.

Another case from July 2013 contained an important declaration from Cayman Islands Chief Justice Anthony Smellie with regard to child custody in divorce matters, the specific case involving the custody of a five-year-old girl.

“There is no presumption that the child must reside with one parent or the other,” the chief justice wrote in his decision on the case. “Her tender age and gender may be important considerations strongly supporting a more suitable arrangement for residence with her mother, but they are not conclusive.

“Ultimately, what will generally be in her best interests will be determinative of the arrangements to be made.”

Such matters, Mr. McCormac said, will end up setting guidelines for similar matters that judges use in their decisions on future cases and may be of interest to the general public. However, he said protecting the identity of participants in Cayman Islands cases will be more difficult than in larger jurisdictions.

“In a small country, like ours, that’s more of a challenge,” Mr. McCormac admits.

It is, at least partly, for that reason that the Cayman Islands court system did not follow what had already been done with the family courts of England and Wales. Mr. McCormac said the courts there typically release almost all family court judgments to the public.

In the local scenario, only Grand Court case judgments would be released, not those that come before the Summary Court. In addition, the judges themselves will maintain sole discretion over which rulings are made public, Mr. McCormac said.

Wednesday, February 19, 2014

Bond Unreliable to Deter Potential International Child Abduction

by

Jeremy D. Morley

A Florida appeal court has sensibly overturned a

lower court’s decision that had allowed the visit of two children to Jamaica to

see their father conditioned primarily on his filing a $50,000 bond.

The father had been deported to Jamaica upon

convictions for battery on the mother and had repeatedly threatened to kidnap

the children.

The appeal court stated that the trial court’s

concern about a potential abduction was well founded, but ruled that “its

decision to address that concern through a monetary bond is not. Given the fact

that Jamaica is not a signatory to the Hague Convention, there is no evidence

suggesting that the mother would be able to gain return of the children from

Jamaica through legal processes, no matter how much money was available to her

from a bond…. Nor would the evidence support a finding that the bond, standing

alone, could deter a potential kidnapping given the father's demonstrated

disregard for the law and repeated threats to take the children from the

mother.” Matura v. Griffith, --- So.3d ----, 2014 WL 338750 (Fla.App. 5

Dist.,2014).

We have repeatedly warned that, since children are

priceless, bonds are never “painful” enough to overcome the decision that

parental abductors often make that – at any and all cost -- their child should

be away from the other parent and with their family in their country of origin.

While bonds may provide a litigation war chest they will not even provide much

value in that regard unless the foreign legal system is likely to take action,

as the Florida court has now usefully recognized.

Friday, February 14, 2014

Turkish Family Law

I had the great pleasure and privilege recently of

addressing the First Turkish-American Lawyers Conference at New York Law School

on the topic of “Turkey and

International Family Law.”

My particular focus was on Turkey and international child

custody matters, especially:

-Relocation of children from Turkey to the United States.

-The recovery of children abducted from Turkey to the United

States, focusing on the Hague Convention and the Uniform Child Custody

Jurisdiction & Enforcement Act.

-Preventing the abduction of Children to Turkey.

-Securing permission for children to visit Turkey.

-Recovery of children abducted from the United States to

Turkey.

-The use of expert witness on Turkey’s family law in such

cases.

Wednesday, February 12, 2014

Book Review: The Hague Abduction Convention by Jeremy D. Morley

2-FEB Colo. Law. 60

Colorado Lawyer

February, 2013

Department

Reviews of Legal Resources [FNa1]

Book Review

*60 THE HAGUE ABDUCTION CONVENTION: PRACTICAL ISSUES AND PROCEDURES FOR FAMILY LAWYERS BY JEREMY D. MORLEY 404 PP.; $149 ABA PUBLISHING, 2012 321 N. CLARK ST., CHICAGO, IL 60610-4714 (800) 285-2221; WWW.ABABOOKS.ORG

Review of Morley on The Hague Abduction Convention

February, 2013

Department

Reviews of Legal Resources [FNa1]

Book Review

*60 THE HAGUE ABDUCTION CONVENTION: PRACTICAL ISSUES AND PROCEDURES FOR FAMILY LAWYERS BY JEREMY D. MORLEY 404 PP.; $149 ABA PUBLISHING, 2012 321 N. CLARK ST., CHICAGO, IL 60610-4714 (800) 285-2221; WWW.ABABOOKS.ORG

Review of Morley on The Hague Abduction Convention

Here is a review of my book on The Hague Abduction Convention: Practical Issues and Procedures for Family

Lawyers.

A family law attorney--and even a district judge--may go his

or her entire career having never dealt with the issue of international child

abduction. Should the issue ever arise, there would

be no better book to have on a law library shelf than Jeremy

Morley's

The Hague Abduction Convention: Practical Issues and Procedures for Family

Lawyers. Morley, an international family law attorney working in New York,

has applied his experience with the Hague Convention on the Civil Aspects of

International Child Abduction (Convention) to write a trenchant and valuable

guide useful to advocates and adjudicators.

The Convention deals with a narrow

question of law: when must a child who was abducted from a country in which a

person other than the abductor had a right of custody be returned to that

country? This is a narrow question, and it is one that could have incredible

implications. For example, many child abductions frequently arise from mothers

fleeing domestic violence. In other cases, custodial parents in international

relationships find the relationship does not work and one parent then tries to

find a way home with his or her child or children. The children caught in these

situations may be subjected to psychological and even physical harm. Therefore,

any attorney dealing with an international child abduction will want to make

sure he or she has a firm grasp of the applicable law. Morley gives them that

grasp.

The book's structure is sensible and

utilitarian. It opens with the Conventions history, policy rationales, and

processes (at a very high level of generality). Morley explains the

requirements a petitioner must meet to make a claim under the Convention: that

the petitioner has custody rights and that the child was taken from a country

of habitual residence. Having explained the basis for petitions under the

Convention, Morley next turns to common shields to defend against petitions.

The book's substantive sections close by considering situations in which a

habitual residence is not a signatory to the Convention or mere international

travel may turn into international child abduction. Several appendixes

containing the Convention, enabling legislation, and the official commentary

follow the substantive sections.

The strongest selling point of the

book is the author's ability to guide readers through American and

international case law for the benefit of both petitioners and respondents. For

any of the issues in which there is a divergence of law, the reader finds the

most frequently cited cases in favor of and opposing each of the viewpoints.

Where the law is clear but fact-driven, Morley provides citations to cases that

draw out key analogous facts for the advocate representing the petitioner or

respondent in an abduction case. In doing so, he eases the path forward for

attorneys unfamiliar with this area of law.

The book's target audience is

attorneys litigating international child abduction cases; however, it also is a

worthwhile read for anyone advising immigrants, prospective expatriates, and

service members. For example, a client in these groups with children may have

orders to make a permanent change of station overseas or may decide to move

home. Proactive attorneys may preempt Convention litigation by ensuring that

parenting plans for these clients include consent to bring a child overseas or,

in the alternative, expressly withholding that consent. At the very least, this

will build a record for later petitions under the Convention.

If there is one criticism that can

be lodged against the publication it is that the accompanying CD adds little if

any value, and simply may drive up the retail cost of the book. The CD merely

provides electronic access to the seven appendixes in PDF format. The

information otherwise can be found online through a simple electronic search or

it should be familiar to a family law practitioner (as in the case of the

Uniform Child Custody Jurisdiction Act).

Model Rabbinic Leadership

By Rachel Levmoe

02/05/2014

Jewish communities the world over can, and should, stamp out the agunah problem.

A striking demonstration of true rabbinic leadership was unveiled this week, in what may be the most unlikely of countries. One would expect creative rabbinic rulings for the good of an entire community to emanate from the great centers of Jewish study such as can be found in Jerusalem or Lakewood. However, reality disabuses us of that notion.

The larger the Orthodox community, the more conservative its rabbis.

Not so Rabbi Ben-Tzion Spitz, chief rabbi of Uruguay.

As a graduate of Yeshiva University with a master's degree in mechanical engineering from Columbia University, he obviously knows to discern cause and effect. Less than a year in office, Rabbi Spitz has been confronted with a growing number of agunot - women whose husbands refuse to arrange for a Jewish divorce by granting them a get.

Deeply disturbed by the plight of the women chained in Jewish marriage to a man wielding the ultimate weapon in his power - get-refusal - he was receptive to an initiative launched by Sara Winkowski - a director of the "Kehila" (Jewish Community of Uruguay) - for the resolution of the agunah problem.

Chief Rabbi Spitz not only authorized the use of a prenuptial agreement designed to prevent get-refusal, he mandated its use. A result of a process involving the community through a legal committee, the prenuptial agreement is supported by the board of directors of the Kehila. The document follows both Jewish and Uruguayan law.

There are an estimated 10,000 Jews living in Uruguay.

Many, who are not necessarily observant, prefer to have an Orthodox wedding.

However, the agunah problem crops up in marriages performed specifically in accordance with Orthodox Jewish law. Without a get given to the wife under the auspices of an Orthodox rabbinical court, a civilly divorced woman is not free to remarry under Jewish law.

Interestingly, although the community is a Zionist one, enjoying close relations with the Israeli rabbinate, the local rabbinate did not choose to turn for assistance to Israel. Viewing this as a community problem with the need for a community-based solution, Chief Rabbi Spitz provided one.

Recognizing his responsibility for the welfare of his female constituents, Rabbi Spitz said: "By instituting the wholesale signing of the prenuptial agreement, and without discriminating between couples who may or may not choose such insurance, we have presented a solution to this long-standing problem for all families that will marry under the auspices of the Kehila."

In order to provide protection to all women getting married under the Orthodox wedding canopy, the Kehila will not conduct marriages of couples that will not sign the Rabbinic Prenuptial Agreement. The Kehila is actually the keeper of a registry of Jewish weddings in the community dating back to the year 1950, which is the basis for issuing certificates of Judaism.

This is one of the few ways for Jews from Uruguay to be recognized as Jews by the State of Israel.

Pressing the point even further, to ensure that every couple marrying in an Orthodox manner does indeed sign the prenuptial agreement, the Kehila will no longer enter into the registry or issue certificates of Judaism to families that do not participate in the signing of the prenuptial agreement. This model of rabbinic leadership deserves to be positively lauded.

In contemporary society, leading rabbis tend to stay away from preventative solutions.

It takes the small Jewish community of Uruguay, together with its local communal institution - the Kehila - and its chief rabbi, Ben-Tzion Spitz, to teach us all a lesson. Jewish communities the world over can, and should, stamp out the agunah problem.

http://www.jpost.com/Opinion/Op-Ed-Contributors/Model-rabbinic-leadership-340481

02/05/2014

Jewish communities the world over can, and should, stamp out the agunah problem.

A striking demonstration of true rabbinic leadership was unveiled this week, in what may be the most unlikely of countries. One would expect creative rabbinic rulings for the good of an entire community to emanate from the great centers of Jewish study such as can be found in Jerusalem or Lakewood. However, reality disabuses us of that notion.

The larger the Orthodox community, the more conservative its rabbis.

Not so Rabbi Ben-Tzion Spitz, chief rabbi of Uruguay.

As a graduate of Yeshiva University with a master's degree in mechanical engineering from Columbia University, he obviously knows to discern cause and effect. Less than a year in office, Rabbi Spitz has been confronted with a growing number of agunot - women whose husbands refuse to arrange for a Jewish divorce by granting them a get.

Deeply disturbed by the plight of the women chained in Jewish marriage to a man wielding the ultimate weapon in his power - get-refusal - he was receptive to an initiative launched by Sara Winkowski - a director of the "Kehila" (Jewish Community of Uruguay) - for the resolution of the agunah problem.

Chief Rabbi Spitz not only authorized the use of a prenuptial agreement designed to prevent get-refusal, he mandated its use. A result of a process involving the community through a legal committee, the prenuptial agreement is supported by the board of directors of the Kehila. The document follows both Jewish and Uruguayan law.

There are an estimated 10,000 Jews living in Uruguay.

Many, who are not necessarily observant, prefer to have an Orthodox wedding.

However, the agunah problem crops up in marriages performed specifically in accordance with Orthodox Jewish law. Without a get given to the wife under the auspices of an Orthodox rabbinical court, a civilly divorced woman is not free to remarry under Jewish law.

Interestingly, although the community is a Zionist one, enjoying close relations with the Israeli rabbinate, the local rabbinate did not choose to turn for assistance to Israel. Viewing this as a community problem with the need for a community-based solution, Chief Rabbi Spitz provided one.

Recognizing his responsibility for the welfare of his female constituents, Rabbi Spitz said: "By instituting the wholesale signing of the prenuptial agreement, and without discriminating between couples who may or may not choose such insurance, we have presented a solution to this long-standing problem for all families that will marry under the auspices of the Kehila."

In order to provide protection to all women getting married under the Orthodox wedding canopy, the Kehila will not conduct marriages of couples that will not sign the Rabbinic Prenuptial Agreement. The Kehila is actually the keeper of a registry of Jewish weddings in the community dating back to the year 1950, which is the basis for issuing certificates of Judaism.

This is one of the few ways for Jews from Uruguay to be recognized as Jews by the State of Israel.

Pressing the point even further, to ensure that every couple marrying in an Orthodox manner does indeed sign the prenuptial agreement, the Kehila will no longer enter into the registry or issue certificates of Judaism to families that do not participate in the signing of the prenuptial agreement. This model of rabbinic leadership deserves to be positively lauded.

In contemporary society, leading rabbis tend to stay away from preventative solutions.

It takes the small Jewish community of Uruguay, together with its local communal institution - the Kehila - and its chief rabbi, Ben-Tzion Spitz, to teach us all a lesson. Jewish communities the world over can, and should, stamp out the agunah problem.

http://www.jpost.com/Opinion/Op-Ed-Contributors/Model-rabbinic-leadership-340481

Monday, January 27, 2014

Left Behind: Parents Challenge Japan's Dismal Child Abduction Laws

It sounds like something out of a

John Grisham novel—but it’s not.

“The gentleman was here on a holiday

in January 2013 with his family,” explains Bruce Gherbetti, deputy chairman of

Kizuna Child-Parent Reunion, discussing the case of a Canadian man who had

reached out to their organization after his Japanese wife abducted their son.

“During the second week of their vacation he went to have a shower, and when he

got out—they were gone. He hasn’t heard from his wife since and has no idea

where they might be.”Sadly, the man’s case is just one of many on Kizuna’s books. The organization, an NGO pressing to restore parent-child rights in Japan, specializes in helping “left-behind” parents deal with child abductions to—and within— Japan by their spouses. Kizuna chairman John Gomez estimates there have been about 3 million parental child abductions in Japan since 1992. Gomez himself is a left-behind parent, or LBP. “That’s roughly 150,000 cases per year, and every one of those is a human rights violation,” the soft-spoken Gomez says. “I took data from the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare and looked at divorces in Japan from 1992-2011. Primetime NHK news program Close Up Gendai in September 2010 [also] suggested 58 percent of parents lose access to their children after divorce. This is being acknowledged and recorded as an accurate estimate and translates to 1-in-6 children in Japan having lost a parent through divorce.”

Its divorce figures may be consistent with rates worldwide, but Japan is unique in that child abduction after separation or divorce is legal according to its family court. Only one parent is recognized as having shinken (parental rights) with the other expected to forgo all parental privileges.

While the vast majority of cases concern Japanese couples, globalization has seen an increasing number of intercultural relationships in which children can effectively be snatched from their non-Japanese home country and brought to Japan—no questions asked.

Although Japan unanimously passed legislation to allow it to join the Hague Convention on the Civil Aspects of International Child Abduction in the spring of 2013, it only applies to future cases. There are also doubts among left-behind parents, lawyers and others alike that not much will change unless domestic laws are also addressed.

Gherbetti is one of the skeptics. “The implementing legislation Japan has passed to accede to the Hague Convention is flawed in many ways. It allows for big loopholes in and around the non-return of children, specifically concerning Article 13(b), which states that if there’s a grave risk to a child, then that child shouldn’t be returned to their country of habitual residence. Japan’s legislation…adds categories where they can deny the return of a child abducted to Japan post-ratification.” According to Gherbetti, a similar scenario exists with the legislation Japan has passed concerning visitation and access.

To that end, Kizuna seeks to become an authorized service provider with permission to implement and facilitate visitation under the Hague Convention in Japan, which requires cooperation between governments and professional experts versed in child-parent reunion issues. It’s part of the organization’s charter to focus on solutions, say Gomez and Gherbetti—yet Kizuna acknowledges that changes to local laws will make more of a difference.

“I think Japan has agreed to sign and implement the Hague Abduction Convention primarily to reduce the pressure from the United States, which has been ramped up over the last four years. When Japan accedes, it will be the 90th country to join the Convention and the last of the G8 countries to do so. But will they be compliant? Probably not,” says Gherbetti.

“On the other hand, legislation has just been approved unanimously in the US House of Representatives—House Resolution 3212: Sean and David Goldman International Child Abduction and Return Act of 2013—which gives the president the opportunity to sanction and penalize member countries that are non-compliant with the Hague. I think the gaiatsu [outside pressure] is going to have to remain to ensure Japan is partially compliant.”

Indeed, in mid-December, the House voted to create an annual report to assess child abductions across all countries, and to require President Barack Obama to take action against nations who remain noncompliant. Potential US measures include refusing export licenses for American technology, slashing development assistance and postponing scientific or cultural exchanges. However, the final decision on whether to proceed with punishment would remain with the president. And then there remains the situation with domestic Japanese law and policy.

“The Japan family court system is the root cause of international and domestic abduction cases alike,” says Gomez. “Both kinds of cases are interlinked as the family court ignores foreign court orders and visitation is not enforced. This is despite Japanese Civil Code Article 766 taking effect in April 2012. It requires boxes be checked on divorce forms stating that parents have agreed to a child visitation plan—and that there have been discussions on child support payments—but Kizuna has found via government data that while most divorces go through, only 50 percent of people getting a divorce check the boxes and there’s no follow-up to see whether they comply.

“Furthermore, the family court continually validates claims of domestic violence without thorough investigation and always gives sole custody to the parent who has abducted the children.”

It’s a point that international family attorney Jeremy Morley, based in New York City, says is a sticking point, describing sole custody akin to “’finders keepers, losers weepers’ in its rawest and most cruel form.”

He also mentions the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child. Japan signed that treaty two decades ago, yet has failed to comply with its principles when it comes to parent-child abductions.

This lack of compliance and ignoring of foreign court orders is something Japanese national Masako Aeko Suzuki knows only too well. Married, living in Canada and mother to a boy, Kazuya David Suzuki, her marriage broke down in the mid-2000s. “My husband, a Japanese, abducted our then 12-year-old son to Japan in 2006,” she recalls. “This was despite the Hague Convention, which I only learned about after my son was kidnapped. A Canadian court also ruled for joint custody and that my son not be forcibly taken to Japan, but by the time this ruling came through, it was too late.”

Masako retuned to Japan and tried to find her son. She struggled with the archaic family law system and its requirements. She learned of other LBP in Japan and was particularly struck by the international cases, given the circumstances under which her own son was abducted.

She reckons she has spent over $100,000 on legal fees both in Canada and Japan and has taken her case to the high and Supreme courts. “My ex-husband Jotaro Suzuki was granted sole custody of my son by the Japanese family court in late 2006; this is standard for abduction cases. I was later granted very brief visitation rights, but Jotaro and Kazuya again disappeared and I haven’t heard from them since.

“In order to apply for further visitation rights, I had to supply my son’s address as per the jyuminhyou (official address registration), but I didn’t know where he was because he’d been kidnapped! It doesn’t make sense!”

Ms. Suzuki admits to being broken, but not defeated. “[Since returning to Japan] I decided to establish my own organization, Left Behind Parents Japan, to help other struggling LBP.” Part advocate, part translator, part interpreter and part counselor, her workload has only increased.

It’s a similar situation at Kizuna, say Gomez and Gherbetti. Future goals are to recruit more volunteers and ramp up fundraising, educate Japanese public about the global standard of joint custody and reconnect children with their left-behind parent while honoring their best interests.

Says Gomez, “This work to reunite children with their parents and change the system in Japan is my life’s mission. We have targets and milestones we’d like to achieve, such as enforceable visitation rights and guidelines for reasonable terms of visitation that permit a parent to maintain a relationship with their child, throughout separation and divorce. That means the amount of hours is sufficient; typically, visitation hours in Japan equate to only one to two hours per month. After that, eventually we’ll look at joint custody, and denial of access should be criminalized. I don’t know how long it will take to change that, but I’ll be working on that indefinitely.”

Hague Convention

The 1980 Hague Convention on the

Civil Aspects of International Child Abduction works to ensure the prompt

return of abducted children to their country of habitual residence. It does so

by compelling its signatories to respect the custodial rights of the left-behind

parent.If Japan were a signatory, the Japanese courts would be obliged to order the return of children to their country of habitual residence prior to the abduction. Instead, as is almost always the case in Japan, the court orders a new hearing so that it can decide custody (disregarding previous decisions), which is exactly what the Hague Convention seeks to avoid.

Glimmers of Hope?

Says Gomez: “In terms of enforcement

of visitation, we’re starting to see an inkling of the beginnings of

enforcement. This is because in March 2013, a Japanese Supreme Court ruling

upheld a Hokkaido High Court ruling that financial penalty for failure to

comply with a visitation agreement was legal. Optimistically, I hope this

brings about systemic change.”

Warning Signs

Many of the people interviewed for

this story said it was difficult to pinpoint any signs separate to general

marital discord that suggest one’s partner may be considering abducting their

children. Bruce Gherbetti sums it up thusly:“I don’t know if there are any warning signs per se that would differentiate a potential abductor from someone who’s just in an unhappy marriage, but one of the things that people might want to be wary of is the issue of separation itself. From my own personal experience, I wouldn’t recommend talking about separation. That could possibly tip someone into abducting.”

The Children’s Rights Network (see below), a treasure trove of information on child abduction on the internet, has also published a useful parental abduction preparedness checklist.

Rights of the Child

“The U.N. Convention provides that

countries shall use their best efforts to ensure recognition of the principle

that both parents have common responsibilities for the upbringing and

development of the child. Unfortunately, Japan’s legal system does not

adequately protect this right. In Japan it is rare for a court to effectively

enforce the fundamental human right of both parents after a divorce to have a

significant role in the life of their children (and the fundamental human right

of children to have both parents in their lives). This will likely make it

difficult for the Japanese courts to effectively implement the Hague Abduction

Convention.”—international family law attorney Jeremy Morley.

Thursday, January 09, 2014

Australia: Asset Division on Divorce

Jeremy

D. Morley

In an important ruling the Full Court of the Family

Court of Australia at Sydney has distinguished, if not overturned, a line of

cases whereby a judge could make an unequal distribution of the parties’ assets

if the party to be favored had made a “special contribution” based on “special

skills” to the creation of such assets. Kane & Kane, [2013] FamCAFC 205.

The parties were married for 28 years and in a

relationship for almost 30 years. Their assets totaled $4.2 million, of which $3.4 million was

held in a retirement fund. The couple initially contributed equal amounts to

the fund, but the husband decided to invest a large proportion in shares

against the wife's wishes, leading to a significant profit. Section 79 of Australia’s Family Law Act 1975 gives a court a broad discretion to allocate the assets of divorcing parties, based inter alia on their respective contributions to the acquisition, conservation or improvement of assets, and to the welfare of the family.

Because of his ''skill in selecting and pursuing the investment'', the trial judge had awarded the husband two-thirds of the retirement fund, or $1 million more than the wife. All other assets - totaling less than $800,000 - were divided equally.

While prior cases had paved the way for such an analysis, the Full Court declared that it was wrong to place “unacceptable weight” on the “special skills” of one spouse and remanded the case for a new hearing in which the court’s discretion should be applied by considering all of the parties’ financial and non-financial contributions throughout the entirety of their relationship.

The case means that a wealthier spouse who divorces in Australia after a long marriage is less likely to walk away with a disproportionately higher share of the parties’ assets.

Wednesday, January 08, 2014

Child Custody in Israel: Religious or Secular Courts?

Child custody matters in Israel can be handled by

religious or secular courts depending on the religious affiliations of the

parents. The article below describes a situation where the nature of those

affiliations is disputed and both secular and religious courts become involved.

High Court freezes ruling by Shari’a appeals court in

child custody dispute

By Yonah Jeremy Bob 01/08/2014

The High Court of Justice on Tuesday issued an

interim freeze against an order of the Shari’a Court of Appeals in Israel that

would have led to transferring custody of two children from the mother to the

father in a custody battle.

The conflict pits the civil court system against the Shari’a courts (which can serve Muslims living in Israel), with the Jaffa Shari’a Court having said it can overrule a prior decision of the Haifa District Court granting temporary custody to the mother.

According to a Justice Ministry statement, the facts of the case are as follows: The couple married in 1999 and have two children, ages nine and 13.

The couple split after the husband started physically abusing the wife, with the wife running away from their home in the North with their two children to live in the central region.

In 2008, the mother filed a request with the Kiryot Family Court to obtain custody of the children as well as alimony and maintenance payments from the father.

There was significant litigation on the issues before the Kiryot court and a number of social-worker evaluations of the parents, with the court granting the mother temporary custody and obligating the father to undergo further tests regarding his competence as a parent.

Following the father’s failure to cooperate with the officials empowered to evaluate him and with the court in general and his failure to pay maintenance per the court’s order, the court froze the case (with the children in the indefinite temporary custody of the mother) until the father came into compliance with the court’s directives.

Simultaneously, the father initiated parallel custody proceedings before the Jaffa Shari’a Court, in which he contended for the first time that the mother was a Muslim.

While there is no dispute that the father is Muslim, the mother has always claimed to be unconnected to any religion and the father insisted on moving the kids into Muslim schools whereas they have been learning in secular state schools for years.

In parallel, the Jaffa Shari’a Court granted the father custody while the Haifa District Court upheld the Kiryot Family Court ruling in favor of the mother and said that the shari’a courts had no jurisdiction.

However, following the father’s ignoring that ruling and obtaining a ruling from the Shari’a Court of Appeals that the Shari’a courts had jurisdiction, the Haifa District Court told the mother that she could only obtain further relief from the High Court.

The Justice Ministry’s Legal Assistance Division on Monday filed a petition with the High Court that quickly blocked any continuation and enforcement of the Shari’a courts’ proceedings until it decides whether custody should be decided in the civilian or the Shari’a courts.

The petition’s ultimate goal is to void all Shari’a court decisions on the issue and to uphold the civilian courts’ decisions in favor of the mother.

The conflict pits the civil court system against the Shari’a courts (which can serve Muslims living in Israel), with the Jaffa Shari’a Court having said it can overrule a prior decision of the Haifa District Court granting temporary custody to the mother.

According to a Justice Ministry statement, the facts of the case are as follows: The couple married in 1999 and have two children, ages nine and 13.

The couple split after the husband started physically abusing the wife, with the wife running away from their home in the North with their two children to live in the central region.

In 2008, the mother filed a request with the Kiryot Family Court to obtain custody of the children as well as alimony and maintenance payments from the father.

There was significant litigation on the issues before the Kiryot court and a number of social-worker evaluations of the parents, with the court granting the mother temporary custody and obligating the father to undergo further tests regarding his competence as a parent.

Following the father’s failure to cooperate with the officials empowered to evaluate him and with the court in general and his failure to pay maintenance per the court’s order, the court froze the case (with the children in the indefinite temporary custody of the mother) until the father came into compliance with the court’s directives.

Simultaneously, the father initiated parallel custody proceedings before the Jaffa Shari’a Court, in which he contended for the first time that the mother was a Muslim.

While there is no dispute that the father is Muslim, the mother has always claimed to be unconnected to any religion and the father insisted on moving the kids into Muslim schools whereas they have been learning in secular state schools for years.

In parallel, the Jaffa Shari’a Court granted the father custody while the Haifa District Court upheld the Kiryot Family Court ruling in favor of the mother and said that the shari’a courts had no jurisdiction.

However, following the father’s ignoring that ruling and obtaining a ruling from the Shari’a Court of Appeals that the Shari’a courts had jurisdiction, the Haifa District Court told the mother that she could only obtain further relief from the High Court.

The Justice Ministry’s Legal Assistance Division on Monday filed a petition with the High Court that quickly blocked any continuation and enforcement of the Shari’a courts’ proceedings until it decides whether custody should be decided in the civilian or the Shari’a courts.

The petition’s ultimate goal is to void all Shari’a court decisions on the issue and to uphold the civilian courts’ decisions in favor of the mother.

Tuesday, January 07, 2014

BBC Interview with Jeremy Morley on International Prenuptial Agreements

Breaking up is hard to do —

financially

Andrea

Murad, 7 January 2014

Prenuptial

agreements around the world...

Planning a

wedding is stressful enough, so for many couples, considering how they would

handle the financial fallout of a split is hardly on their minds ahead of the

big day.

But that

might be changing. With a growing number of international marriages has also

come an increase in the prevalence of prenuptial agreements, say some lawyers

who specialise in matrimonial law.

A

prenuptial agreement or ‘pre-nup’ is a legally binding contract which can

outline how finances and possessions would be split and handled if a couple

divorce. In some countries, these agreements have existed for hundreds of years

while in others, they’re relatively new. In addition to protecting each

partner’s assets, these agreements can be designed to protect family money,

companies or real estate.

“One reason for a pre-nup is to create clarity and

protection of wealth and assets — clarity, that is to have a clear arrangement

on how the family partnership will operate,” said Jeremy Morley, an

international divorce lawyer based in New York.

Morley said pre-nup discussions can open the door to how

couples expect to run their financial affairs during their marriage. “All over

the world, people don’t talk about money, but it’s very hard to predict the

future and how relationships will change,” he added.

Without a

pre-nup, the courts will decide how marital assets are divided after a split

according to a country’s laws. “Pre-nups are insurance policies against high lawyer

fees,” said Randy Kessler, partner at Kessler & Solomiany, a law firm in

Atlanta. In Kessler’s opinion it is unlikely that the other side will spend a

lot of money if a pre-nup exists.

But before

entering into a pre-nup, spouses need to consider which assets they want to

protect or the financial support they would need to maintain their current

lifestyle if they were to separate from their partner. Agreements can also

include sunset provisions that will make the pre-nup invalid after a certain

period of time. And married couples can even enter into a post-nuptial

agreement after they are married that acts in a similar way to a pre-nup.

BBC

Capital spoke to family law lawyers in the United Arab Emirates, France,

Germany, Japan and the US for more information about how these agreements work

around the world. Scroll through the images above to see the ins-and-outs of

pre-ups in those countries.

United

Arab Emirates: Sharia law and contractual obligations...

Only UAE

nationals, or Emiratis, marry under UAE law. The country follows Sharia law,

and this is outlined in the Quran.

In 2012,

according to the UAE National Bureau of Statistics, 8,753 or 59% of the 14,934

marriages were between nationals, while 2,351 or 60% of the 3,901 divorces were

between Emirati couples. For every 3.7 Emirati marriages that year, there was

one divorce.

“Islam provides an entire regime in and of itself,” said

Jeremy Morley, an international divorce lawyer based in New York. “Marriage is

a contract, and you are required to have a contract that will regulate within

the consequences of divorce.”

The

marriage contract under Sharia law is already a type of a pre-nuptial

agreement. It starts with the Mahar (dowry), which has two parts: an

accelerated dowry is paid upfront at the time of the marriage to cover any

wedding expenses and a late dowry is paid at divorce or following the husband’s

death.

To

encourage Emiratis to marry other Emiratis, the late Sheikh Zayed bin Sultan Al

Nahyan, the former UAE president, set a limit on dowries to prevent Emirati

grooms from slipping into debt. Currently, the accelerated Mahar cannot exceed

AED 20,000 ($5,445) and the late Mahar has an AED 30,000 ($8,168) limit — a

total of AED 50,000 ($13,613). Since currency tends to lose value, many brides

ask for this money in gold.

“[The

contract] sets up exactly what the woman will be paid upfront and at the end of

the marriage,” said lawyer and legal consultant Diana Hamade, founder of

International Advocate legal Services based in Dubai. “If the man can prove

that the woman contributed to the end of the marriage, she won’t get paid the

dowry.”

The

husband would have to prove that his wife caused him harm by neglecting him, by

spending too much money or by going out too much, for example. A UAE woman is

able to leave a marriage voluntarily and obtain a Khula. But without being able

to prove harm, she would have to give up everything, including wealth and

children, and repay her husband for everything he had bought for her during the

marriage, Hamade said.

Child

custody and support is not addressed in the marital contract — but these are

very detailed in the law and are not left to the judge’s discretion. Often,

when there are children involved, a woman will usually maintain custody and

manage the children’s day-to-day activities, and from her ex-husband, she will

receive an apartment and child support payments.

Non-Muslim

expats who marry in the UAE will often draft pre-nups that follow the laws of

their homeland.

Germany:

Where pre-nups are more the norm...

United

States: Courts, mediation and complications...

Japan:

Where courts take a back seat...

Most

Japanese couples don’t divorce through the courts. The procedure, called kyōgi

rikon, is very administrative. Couples who agree to divorce instead file

registration documents with a local municipal office. Pre-nups are very rare in

Japan because couples rely on the country’s detailed civil code to determine

how to divide their assets.

Marriage

in Japan is on the decline while the number of divorces has held steady for the

past decade. In 2011, there were about 662,000 marriages and about 236,000

divorces, according to the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare — or

one divorce for every 2.8 marriages that year.

“All the

statutes offer many provisions for divorce,” said Tokyo-based lawyer Hirohito

Kaneko. “The statute of the family court is very clear [regarding] the division

of marital assets.”

In a

divorce, all assets that were acquired during the marriage, excluding any

assets earned prior to the marriage, or any inheritances or gifts, are divided

between each spouse. Japanese law doesn’t provide for spousal support.

“He pays her a modest lump sum just to get divorced,” said

New York lawyer Morley. “That’s usually the end of it — he’s divorced from his

wife and children. There’s very little visitation by the non-custodial parent

in Japan, but this is slowly changing.”

Pre-nups

are more popular in marriages between a Japanese citizen and an international

person. These marriages tend to be more complicated. The couple’s assets could

be spread throughout several different countries, and the couple may decide to

stay in Japan or move to another country in the future.

“Japan has freedom of contract, and [couples] can split

assets however they want — they can make their own deal,” said Morley. “The

civil code in Japan provides that assets created during the marriage are to be

divided equally after the marriage.”

Although

the agreement addresses the division of assets and spousal support, it does not

address issues regarding children, like custody matters and child support.

Child support is determined by the civil code, but is rarely paid and it is

difficult to enforce payment.

To date, there hasn’t been a case that tested pre-nups in

Japan. “It’s very unusual for court cases in Japan to be tested,” said Morley.

“The pre-nup agreement would give more certainty."

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)